It was quite late yesterday evening when a French WhatsApp group of which I am a NPC member suddenly started to scroll with messages. The first of them, the son of a former world champion, shared the news that the legendary cycling journalist Jacques Augendre had died at the age of 99. A rash of mournful emojis followed, and then a member called Eric summed the mood up best of all when he posted, ‘Une page de l'histoire du cyclisme et du Tour de France se tourne...’, which I sincerely don’t believe I need to translate.

I never met Jacques, even though he was still on the race (just) when I started to cover the Tour. His last appearance in the Salle de Presse was in 2004, when he was already in his late seventies. His first had been in 1949, in which he bore witness to Fausto Coppi vanquishing Gino Bartali. It is quite some distance from that race to Lance Armstrong’s penultimate “victory”. Augendre’s was a record breaking span of 55 years at the Tour, which even the mighty Phil Liggett has yet to match.

L’Équipe’s Alexandre Roos, writing in memory of Augendre in today’s paper, reminds his readers of the nature of press reporting from the Tour in an age when there were no TV pictures, and the press used to weave in and out of the race on the back of motorbikes. The Tour was, according to Augendre, ‘a yellow jersey, a cartridge of blue ink and some white paper’; in many ways a novella to be constructed from scratch every day anew. The draft would be scribbled on the back of a motorbike, and then phoned in from the finish line, not from the Salle de Presse, since such a facility was yet to exist. Instead, the journalists would try and blag the use of a phone in town halls, theatres or post offices. Augendre remembers seeing an Italian journalist pissing where he stood in a telephone box, rather than interrupt the copy taking; a process which produced a daily welter of typos and mistakes that the journalists would sigh about over breakfast the following morning when they read their words in print.

Riders would regularly come up to them in the race, and point out what they’d been through in the race. ‘Jacques! You know I’ve punctured twice? Don’t forget to put that in!’ He developed a close relationship with Louison Bobet, with Raymond Poulidor and with Bernard Hinault. Augendre remembered André Leducq, the winner of the 1930 and 1932 Tours recalling how he had been arrested during the war and found to have Resistance leaflets in his briefcase. Incredibly, the German officer recognised him, and let him go. ‘You see, Raymond,’ he would later tease Poulidor in Augendre’s presence, ‘it’s always useful to have won the Tour!’ Poulidor, of course, famously never did.

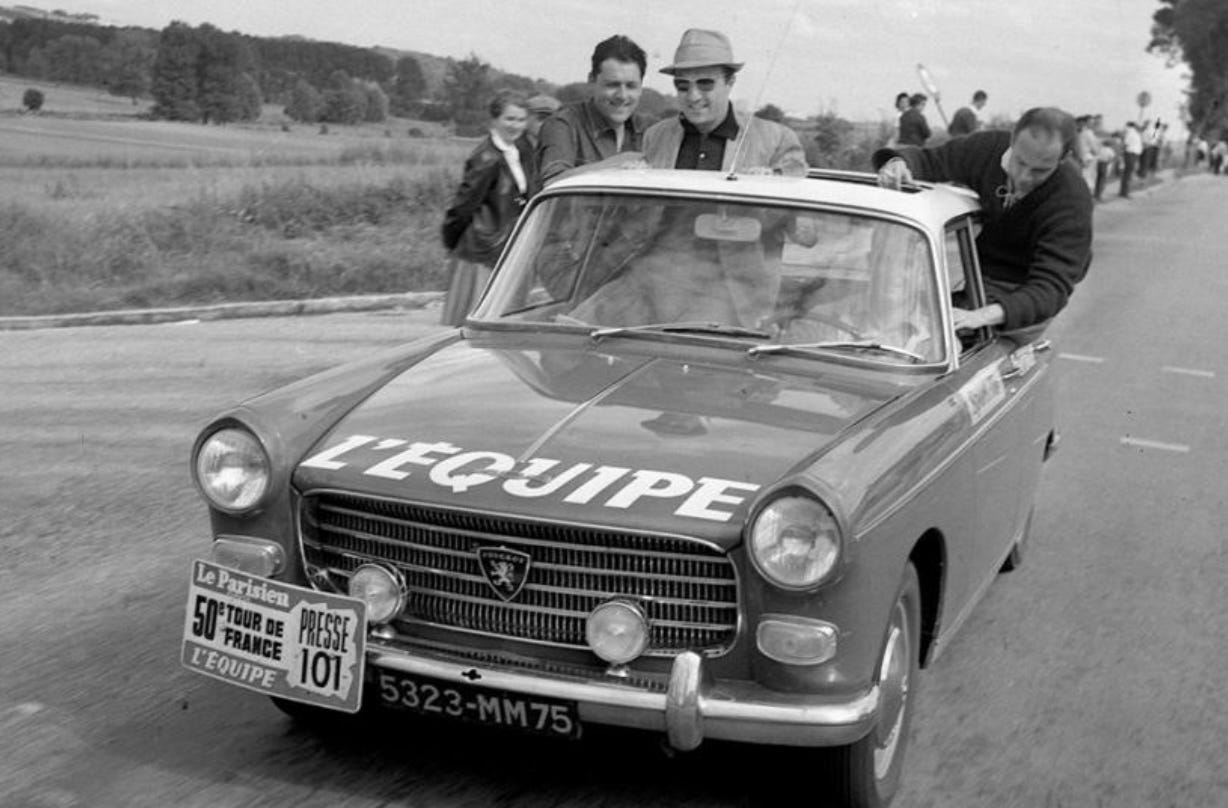

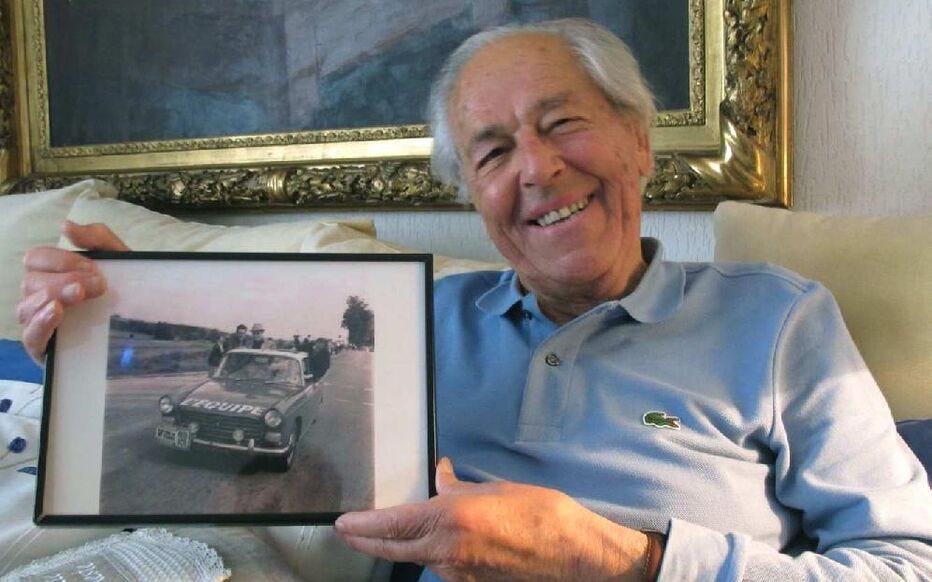

Augendre was also one of four writers who travelled around in the famous red and white Peugeot with the number 101. He’s the one hanging out of the car on the left. A law unto themselves, they were as familiar a sight on the race as Christian Prudhomme’s red car is now. Lunch was a priority, in particular for the great Antoine Blondin (on the right, annoying the driver), whose alcohol consumption was the stuff of legend. One day, staying in the luxurious Hotel Splendid in Bordeaux, Blondin was so drunk that he mistook his ink bottle for Saint Emillion, took a mighty swig of it and proceeded to vomit the ink all over his room. The following morning he bumped into the Race Director Jacques Goddet who was staying in the same hotel, and who was furious with Blondin’s scandalous behaviour. ‘So, Antoine. Pastis and white wine aren’t enough for you any longer? You’re drinking ink now?’

Any of my Substack subscribers who came to see my Marginal Mystery Tour, or have read 1923, will doubtless be familiar with the story of the Pélissier brothers, who grew up in grinding poverty, the sons of an abusive father who worked a subsistence dairy on the outskirts of Paris. There was so little land to graze the herd that the boys were sent to the local parks to rip grass out by hand to feed the cows. The dairy was the last working farm in all of Paris, and had the extraordinary name of Vacherie d’ésperance.

Augendre’s mother grew up near the Trocadero, and as a teenager was sent every day to fetch milk from the Pélissiers’ dairy. He recalled how differently things might have worked out, had his mother succumbed to the “charms” of the famously flirtatious Pélissier brothers. Instead, she fell for Jacques’s father Philippe, a decent rider. Indeed, Jacques himself had a notable amateur career, competing in the wartime 1943 French national championship, won by none other than Raphäel Geminiani. After that, he set his heart on journalism, and went on to write numerous books, including one of the definitive biographies of Fausto Coppi.

I love to read about long and adventurous lives like Jacques’s. The Tour relates to its storytellers in a manner that is unique, I think. Don’t forget that the founder of the race Henri Desgrange was a journalist, and that the current Race Director was a TV commentator at the Tour in a former life. After all, what is a race, without the words to give it colour?

My condolences to the friends and family of Jacques Augendre, who died yesterday, February 18th, 2025. What a life.

Beautiful words Ned.

Lovely piece Ned.